Function Purity

This is a simplified transcription of a talk I gave last week on function purity.

Description: In this session we will talk about why function purity is important and how it can help improve performance, code readability, reduce bugs, and make our code more framework-agnostic.

Hello! My name is Sam and today I'm going to be talking about function purity and why it matters. Before I begin, I thought it would be best if I started with some code examples. I find that looking at the problem head-on is the best way to understand how the solution can be applied. Let's take a look.

What is "function purity" and why does it matter? ¶

let paymentType = 'wallet'

async function emptyCart() {

paymentType = 'credit'

// some async logic

}

async function placeOrder() {

if (paymentType === 'credit') {

// handle credit card

} else {

// handle wallets

}

}

await Promise.all([emptyCart(), placeOrder()])

Here we have sample code of two asynchronous functions, emptyCart and placeOrder. Both are awaited via Promise.all, so we can assume that the order in which these functions execute does not matter - right?

What will happen if emptyCart gets executed before placeOrder? Assuming the remaining asynchronous logic is inconsequential, paymentType will change from "wallet" to "credit". This means that when placeOrder is executed, we will handle the payment type as if it is a credit card.

Likewise, what will happen if placeOrder gets called before emptyCart? When placeOrder gets executed, we will handle the payment type as if it is a wallet because paymentType was never changed. This is a different outcome than the previous example!

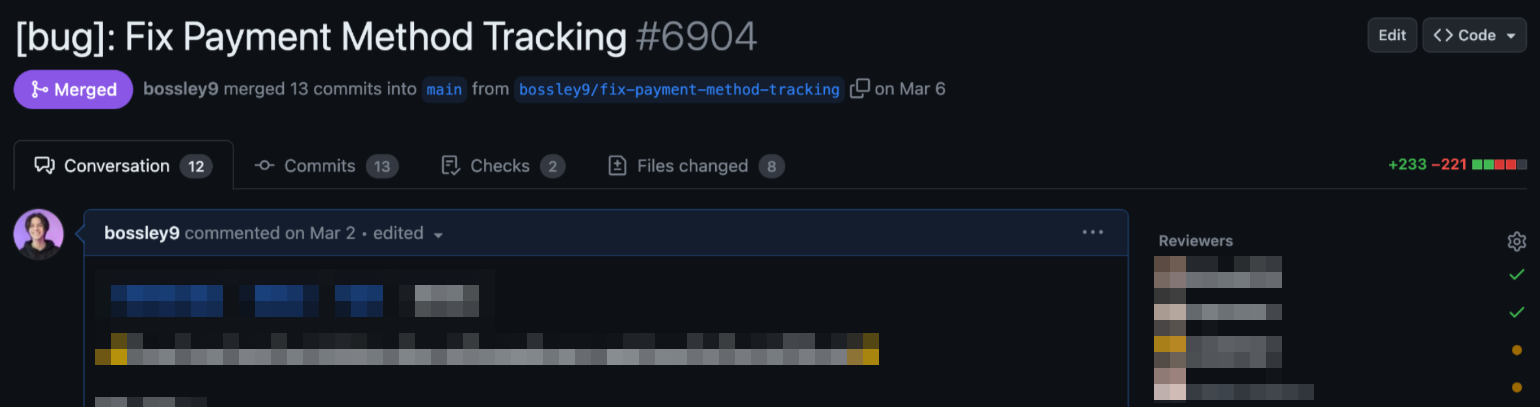

Although both of these functions should be independent the order in which these functions are called affects how they execute. The outcome will be different depending on which function is called before the other. In this example, where the functions are called matters. This may seem like a trivial example, but we had a similar issue in production code only a few months ago where the order in which functions were executed was producing unexpected values.

Here is another illustration:

import { useQuery } from '@tanstack/react-query'

export function useQueryPreferences() {

const userId = useUserId()

return useQuery({

queryKey: [ 'preferences' ],

queryFn: () => fetch('some-api/' + userId),

})

}

export function PreferenceContainer() {

const { data } = useQueryPreferences()

return (

<div>

<p>Email: {data.email}</p>

</div>

)

}

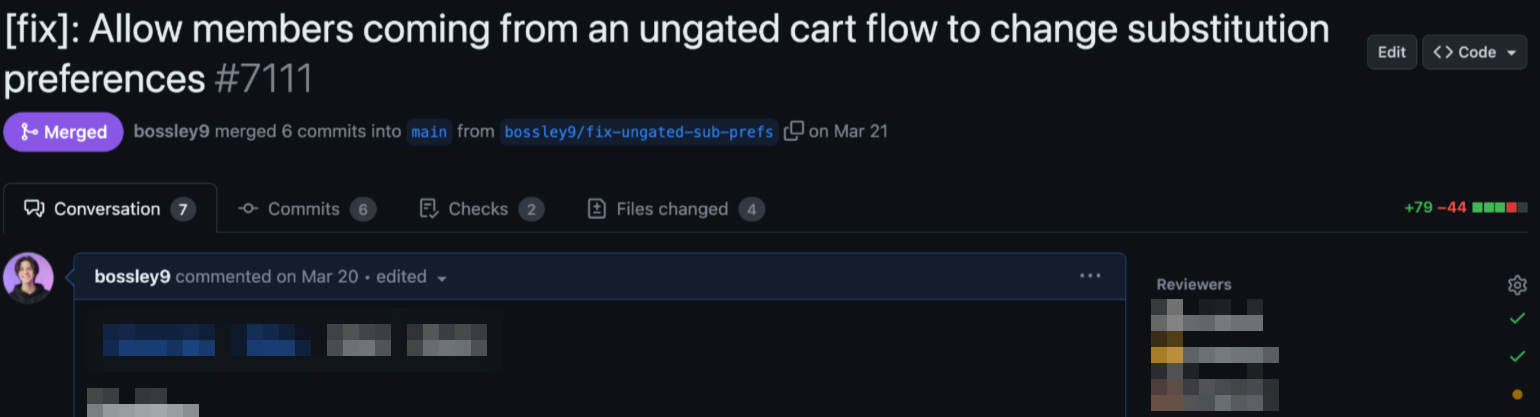

We have a React query function useQueryPreferences which fetches a user's preferences, then a JSX component PreferenceContainer which renders the user's email. On initial component mount, the rendered paragraph tag might read "Email: undefined" because the data will not have been fetched yet. After some indeterminable amount of time, the paragraph tag might read "Email: johndoe@example.com". This doesn't even take into account error states, or what happens inside useUseId. What happens when useUserId returns null or 0? Depending on what time this component renders, it might produce drastically different outputs to the UI. In this example, when the functions are called matters. Again, this reflects another recent production issue where the state of a user's ID value produced unexpected results.

Now that I have highlighted some of the issues function purity can solve, we can now learn what function purity is.

What is a pure function? ¶

By the textbook definition, a pure function is a deterministic function with no dependencies that yields the same output for a given input. In this case, by "deterministic" we mean "predictable and reproducible", and by "dependency" we mean "something that is depended on". Putting all of this together, we can say that a pure function is a predictable and reproducible function that does not depend on anything and yields the same output for a given input.

Pure functions can be thought of as math functions. Take the example y = 3x. We know that when x = 1, y will always equal 3. It doesn't matter when time of day this function is used, or where this function is used, or even how many times this function is used: when x = 1, y will always be 3. Based on this math function, we can notice that pure functions are stateless and produce the same output for the same input at any place or any time. With this knowledge, we can revise our definition of a pure function to this:

A pure function is a function that produces the same outputs for the same inputs anywhere, anytime.

Let us look at some examples:

const mem: Membership = {

type: 'trial',

planID: 14325523,

}

function impureFormatMembershipName() {

if (mem.type === 'trial') {

return `${mem.planID} (trial only)`

}

return `${mem.planID} (${mem.planType})`

}

function pureFormatMembershipName(mem: Membership) {

if (mem.type === 'trial') {

return `${mem.planID} (trial only)`

}

return `${mem.planID} (${mem.planType})`

}

In the above illustration we have two functions: impureFormatMembershipName and pureFormatMembershipName. It's pretty obvious which one is pure solely from the naming convention so let's try to understand why the top function might be impure. If impureFormatMembershipName is called before mem is defined, the resulting string might include the text "undefined". This is because the function is entirely dependent on the declaration of mem. This function cannot be called anywhere because it depends on where it is declared relative to mem.

In contrast, pureFormatMembershipName is pure because it will always return the same value for a given Membership input regardless of where it is called, when it is called, or how many times it is called.

Let us look at another example:

export function ImpureAddressBox() {

const address = useQueryAddress()

return (

<div>

<p>{address.line1}</p>

<p>{address.line2}</p>

</div>

)

}

type Props = { address: Address }

export function PureAddressBox({ address }: Props) {

return (

<div>

<p>{address.line1}</p>

<p>{address.line2}</p>

</div>

)

}

Here we have functions PureAddressBox and ImpureAddressBox, the latter of which consumes a useQueryAddress hook. Notice that these are both React components - React components can be pure functions as well!

The first component is impure because its output JSX depends on the status of the useQueryAddress hook: has it already fetched data, or is it still loading? This function cannot be called anytime because it depends on what state of the address data and how it is returned in the useQueryAddress hook. This example may not be as straightforward as the previous example. You might think that even if we use the pure component, we still need to use the hook in the parent to retrieve address data to pass as a prop to the component. In later examples I will explain how the placement of hooks around pure components can provide significant benefits.

Why does function purity matter? ¶

Why then does function purity matter? As we have seen in the previous illustrations, impure (or stateful) functions have consequences and may lead to unpredictable scenarios. Depending on the timing and location of these function calls, our output may be vastly different than our expectations for the output. Unpredictability in the behavior of our application gives us less confidence that it works.

Now that we have a strong motivator for using pure functions, let us examine some of the benefits that pure functions provide.

Why use pure functions? ¶

1. Reduced bugs ¶

The usage of pure functions automatically guarantees us reduced obvious bugs due to state inconsistencies. Below is an example taken directly from the React website:

let guest = 0

function Cup() {

guest = guest + 1;

return <h2>Tea cup for guest #{guest}</h2>

}

export default function TeaSet() {

return (

<>

<Cup />

<Cup />

<Cup />

</>

)

}

In this illustration, we have two components Cup and TeaSet. TeaSet renders three Cup components with increasing values for the variable guest. Based on the return statements, we might expect the output of TeaSet to be:

<h2>Tea cup for guest #1</h2>

<h2>Tea cup for guest #2</h2>

<h2>Tea cup for guest #3</h2>

Let us verify our claims by examining our output in a React environment.

<h2>Tea cup for guest #2</h2>

<h2>Tea cup for guest #4</h2>

<h2>Tea cup for guest #6</h2>

How did the actual output differ from our expectation? We expected a steady increase in guest number, but each iteration actually increase the value of guest by two. Here lies the issue: we don't know how React renders components internally and how many times our component Cup might render. Because of this, we have no way of knowing exactly what values of guest will appear in the output. To make this component more predictable, we can modify the code to accept guest numbers as a prop:

function Cup({ guest }) {

return <h2>Tea cup for guest #{guest}</h2>

}

export default function TeaSet() {

return (

<>

<Cup guest={1} />

<Cup guest={2} />

<Cup guest={3} />

</>

)

}

In this example, we can predict its output and have more confidence that rendering bugs will not occur. We know that <Cup guest={1} /> will always render <h2>Tea cup for guest #1</h2> no matter where it is called, when it is called, or even how many times it is called.

Here is another example:

const address = useAddress()

const address = getAddress(user)

We can see that the first declaration of the variable address retrieves its value from a hook, and the second declaration receives its value from a pure utility function that accepts a user input argument. What makes these two declarations different is the unpredictability of the hook. Without looking at the implementation of useAddress, we cannot say for sure whether it makes API calls or not. In a simple hook we might look into the hook definition to verify it does not make additional API calls or have any unintended side effects, but imagine a more complex example:

export const useAddress = () => {

const dispatch = useAppDispatch()

const router = useRouter()

const isPickup = useIsPickup()

const storeld = useStoreId()

const storeLocationId = useUserStoreLocationId()

const addressPref = useDefaultShoppingAddress()

const cartPageRoute = useCartSSRRoute()

const { doorDropoff } = useAppSelector(getCheckoutPrefs)

const showDoorDropoff = useShowDoorDropoff()

const selectedPickupLocation = useDefaultPickupLocation()

const { trackCheckoutDetailsClicked, trackCheckoutDetailsUpdated } = useOnTrackCheckoutDetails()

const { mutateAsync: selectStore } = useMutationSelectStore()

const {

mutateAsync: deleteDeliveryInstructions,

isError: hasDeleteInstructionsError,

} = useMutationDeleteAddressDeliveryInstructions()

// ...

}

I would be very impressed if you could tell me how many extraneous API calls this hook makes. By using pure functions and reducing our need for hooks within hooks within hooks, we reduce the possibility of stateful bugs in our codebase.

2. Improved code readability ¶

Let us revisit the previous code example.

const address = useAddress()

const address = getAddress(user)

An additional benefit of using pure functions is improved code readability. In the second declaration, because the function getAddress is pure, we can immediately infer:

addressis a user's address- we are making no additional API calls to get the user's address

- we are creating no additional side effects by fetching the user's address

Pure functions additionally make code easier to read without having to examine definitions.

3. Easier testing ¶

Have you ever seen a large group of mocked out modules when writing Jest tests?

jest.mock('@/components/Checkout/hooks/useOnPlaceNewOrder')

jest.mock('@/services/NewOrder/queries')

jest.mock('@/services/User/hooks')

jest.mock('@/components/Checkout/hooks/usePaymentVerification')

jest.mock('@/components/Checkout/constants')

jest.mock('@/services/ShoppingStore/mutations')

jest.mock('@/components/Checkout/ExpressOrderTotalDetails')

jest.mock('@/utils/dataFetching/reactQuery/useMutationCache')

jest.mock('@/services/Addresses/hooks')

jest.mock('@/components/Checkout/useOnTrackCheckoutDetails')

jest.mock('@/services/DeliveryWindows/queries')

jest.mock('@/services/DeliveryWindows/hooks')

When testing impure functions or components, we tend to mock out all modules that have side effects, resulting in large swaths of mocked modules. Not only does this make our tests confusing to follow, but our testing environment ends up being very different than the output end users will see. If we purify these functions, we will see that virtually no modules need to be mocked because we can write tests to expect static outputs based on static inputs.

4. More framework-agnostic code ¶

The longer you spend working in a tech industry, the more you will learn how fast technologies get replaced. Frameworks and languages will always come and go, but coding practices usually remain the same. Function purity isn't a new concept - in fact, it's been around since the early days of Java. By writing more pure functions, you reduce risk of writing framework-specific code and begin to write more portable code modules that can be adapted to any framework. At the end of the day, React hooks are temporary.

5. Improved performance (potentially) ¶

With pure functions, you may also see some potential performance benefits. Increasing the amount of pure functions generally helps break complex blocks of code into smaller more modular functions. In most frameworks and languages, modules can be code split and cached or memoized. You additionally will reduce the amount of listeners or side effects your application has to monitor. Writing pure functions automatically comes with improved performance benefits without additional hassle!

How to write pure functions ¶

I've already sold you on what pure functions are and why you should use them. What then is the recommended way to write pure functions? How can we learn to write pure functions? You can determine if a function or component is pure by answering these three questions:

- can the function be called anywhere and still produce the same output?

- can the function be called anytime and still produce the same output?

- can the function be called multiple times consecutively and still produce the same output?

If you were able to answer yes to all three questions, your function is pure!

Here is an illustration on how to purify an impure component:

function Child1() {

const { data } = useQueryMyData()

return <span>{data}</span>

}

function Child2() {

const { data } = useQueryMyData()

return <span>{data}</span>

}

export function Parent() {

const { data } = useQueryMyData()

return (

<div>

<hl>Report for {data.name}:</h1>

<Child1 />

<Child2 />

</div>

)

}

When the Parent component renders, we will create three listeners for useQueryMyData even the data passed to Child1 and Child2 never changes. If we convert hook data to function parameters and memoize the child components, we can reduce the number of listeners to one and prevent the children from re-rendering unnecessarily. We now have increased performance and two pure component children!

const Child1 = memo(function({ data }) {

return <span>{data}</span>

})

const Child2 = memo(function({ data }) {

return <span>{data}</span>

})

export function Parent() {

const { data } = useQueryMyData()

return (

<div>

<hl>Report for {data.name}:</h1>

<Child1 />

<Child2 />

</div>

)

}

Pure function caveats ¶

If pure functions provide so many benefits, is there a reason we don't use them anywhere and everywhere in our applications? There are two caveats to consider when examining the purity of a codebase:

1. Applications aren't naturally pure. As was mentioned previously, function purity relies on the underlying principle that the code is predictable and reproducible. However, predictable applications are few and far between: user behavior cannot be predicted or consistent for every user. In this instances, we want to make use of the data listeners and fast reloads that impure code provides to us. The best we can do is scope and restrict the amount of impure code we allow in our codebase.

2. Easier said than done. It's much easier preaching about function purity than actually enforcing it, especially for existing codebases that have historically made abundant use of hooks and data listeners.

Conclusion ¶

We have learned today that a pure function is a function that produces the same outputs for the same inputs anywhere, anytime. We have also learned of some beneficial side effects that come with pure functions such as reduced bugs, improved performance, and easier testing. Pure functions are difficult to implement in practice, and as such, we need to put purity first when implementing new features.

That's all I have on function purity. To get better at writing pure code naturally in frontend feature work, I highly recommend reading "Thinking in React" by React and their thorough article on "Keeping Components Pure".

I also highly recommend reading Clean Code by Robert C. Martin for good advice on how to write more maintainable, cleaner code.

Thank you for listening!